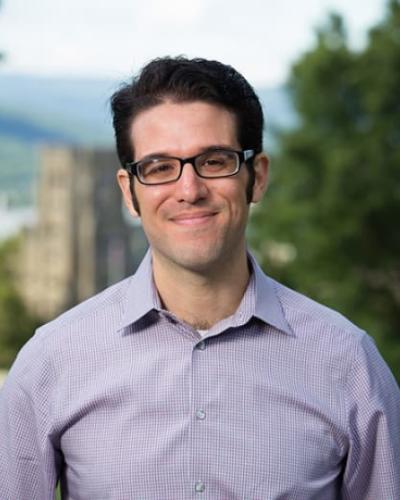

In July 2016, Dr. Matthew Velasco joined the Department of as a Mellon Diversity Postdoctoral Associate and next Fall he will take up the position of Assistant Professor of . In this role, Velasco will help strengthen links among departmental research interests in archaeology, biological anthropology, and medical anthropology. Velasco comes to Ithaca, NY from Vanderbilt University, where he received his PhD and master's degree, both in . He received a Bachelor of Arts degree with Distinction in Anthropological Sciences from Stanford University. An anthropological bioarchaeologist by training, Velasco studies ancient populations of the Peruvian Andes through the analysis of their skeletal remains. He will teach a new course on Bioarchaeology during the Spring 2017 semester. This course combines method and theory from archaeology, forensic anthropology, human biology, and material culture studies to reconstruct how ancient peoples lived and died.

"Matthew for us is the quintessential "high impact" hire. His work will help suture areas of existing expertise in the department—medical anthropology, anthropological archaeology, biological anthropology—while also aiding in our efforts to reach out to other units on campus, including Latin American Studies and the Archaeology Program," said Adam T. Smith, Department of Chair.

Read the interview below or visit Matthew Velasco's faculty page to learn more.

Tell me about your academic journey and how you became interested in anthropology and bioarcheology.

I have always been interested in storytelling. In high school, I dabbled in TV and film production. At one point, I even planned to go to film school; yet I never felt like I truly had a story to tell. introduced me to a world of human stories waiting to be told; stories about human ingenuity and innovation; unspeakable suffering but also the remarkable capacity for survival; unique rituals, traditions, and cosmologies that—however foreign—had something to tell me about my own. Bioarchaeology, the study of human remains from archaeological sites, equipped me with a unique scientific language for reading the stories written on bone, stories that might otherwise be forgotten. Through skeletal analysis I can reconstruct how ancient peoples lived and died; what their childhood was like; what they ate; if they suffered from malnutrition, violence, or disease; how they were treated by others in life and remembered after death. These stories reveal how the major “forces” in human history—from warfare and environmental change, to societal collapse and cultural revolution—are deeply rooted in individual actions, bodies, identities, and experiences.

My journey as an archaeologist began fall quarter of my sophomore year at Stanford University. During a lecture in Introduction to Archaeology, our professor showed the class a 3D flyover model of a three-thousand-year-old ceremonial center in highland Peru. As the camera glided through the labyrinthine underground tunnels of this monumental temple complex, our professor announced funding for a summer program that would allow up to twelve students to accompany him in the field. I was hooked, determined to participate, and eventually earned a spot on the crew. That first trip to highland Peru was in 2006, and I have been returning ever since! Along the way, I wrote a senior honors thesis, gained valuable field and laboratory experience on a number of other projects, directed my own excavations, adopted a Peruvian cat, and completed a PhD at Vanderbilt University.

What excites you about your new position?

I’m thrilled to be a part of such a dynamic and rich anthropology program, and at the same time to have the opportunity to develop a new departmental strength in bioarchaeology. I look forward to training students in skeletal analysis and inviting them to participate in my ongoing field and laboratory work in the southern Andes. There are also exciting plans in the works for the installation of new osteology laboratory that will support a world-class research and teaching program in the analysis of human and faunal skeletal remains. Stay tuned!

What attracted you to Cornell University?

Cornell University has a long tradition in global research and engagement, and I am eager to contribute to it. In particular, the university has a strong legacy in Andean archaeology and anthropology. In the 1950s and 60s, Allan Holmberg created a model for community-engaged anthropology with the Vicos Project. The late John Murra (1916-2006), Professor of , trained dozens of scholars in Andean studies during his time at Cornell, leaving an immeasurable impact on the field in general and on my own work in particular. Alongside such influential scholars as anthropologist and Professor Emerita Billie Jean Isbell, I am honored to continue the Department of ’s rich tradition of research into Andean worlds, past and present.

How do you like to spend your time outside of the office?

My time outside of the office is mostly structured around walking our dog, a Boxer-mix named Jack. During our morning and evening walks, we’ve gotten to know the beautiful sights, smells, and critters that surround our home in Brooktondale. The people here have been especially welcoming, and we’ve enjoyed getting to know our neighbors at community events and meals hosted by the Brooktondale Community Center and Brookton’s Market, our local country store. The small-town life is quite a novelty for someone who was born and raised in southern California, and I’ll be spending a good deal of time this winter shoveling snow and stacking firewood!

What are you teaching in spring 2017? What types of courses would you like to teach in the future?

In spring 2017, I’ll be teaching a 3000-level course on my field of expertise; bioarchaeology. The course introduces students to the array of methodological tools a bioarchaeologist can use to reconstruct life and death in the past. Students will learn scientific techniques for estimating skeletal age and sex, diagnosing pathological and traumatic lesions on bone, and interpreting diet and migration patterns from isotopic and molecular data. Along the way, students will have the opportunity to apply their knowledge of these different techniques to mock case reports, much like a forensic scientist pieces together fragmentary evidence from the scene of a crime.

“Bioarchaeology” is the first in a series of courses that will contribute to the department’s new pathway in Health and Medicine. In 2017-18, I plan to teach a course on “Health and Disease in the Ancient World” that will survey major epidemiological transitions in human history, and also explore different medical traditions and concepts of health and illness. I’m also excited to teach a laboratory-based course in human osteology, the study of bones. It’s an intensive but fun course where students learn how to identify all 206 bones and 32 teeth of the human body.

Why do you think is important?

is important in the globalized world, as our encounters with different peoples and places not only become more frequent, but also increasingly politicized. How do we understand worldviews and life experiences so radically different from our own? How can we then use this knowledge to respond to the needs of the communities in which we live and work? provides the conceptual and practical skills for understanding cultural differences and building bridges between them. This is important in everyday life, but also vital to a myriad of careers paths, from healthcare and medicine to education and social work, to name just a few.