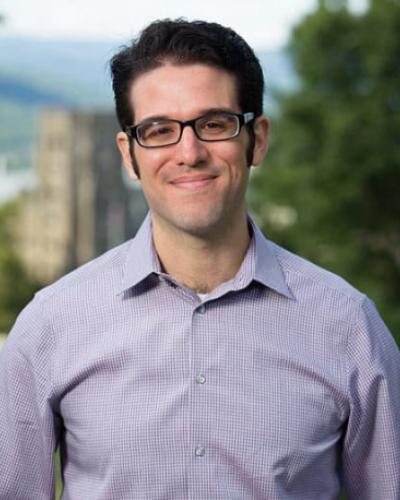

Matthew Velasco, assistant professor in the Department of , has been named a 2020 Career Enhancement Fellow by the Woodrow Wilson National Fellowship Foundation. The Fellowship, funded by The Andrew W. Mellon Foundation, creates career development opportunities for selected faculty fellows with promising research projects.

The Fellowship will support Professor Velasco as he works on his current book project, which revolves around cranial modification, the practice of binding and reshaping an infant’s head.

Professor Velasco shared this project description:

My book project, The Mountain Embodied: Head Shaping and the Making of Personhood in the Ancient Andes, examines how cranial modification emerged historically and helped reshape the boundaries of power and personhood in late prehispanic Peru (A.D. 1000-1532). Drawing from Spanish colonial documents, scholars have typically viewed cranial modification as an emblem of ethnicity under the Inka Empire. From this perspective, differences in head shape, dress, and other so-called ethnic customs marked one “kind of people” as distinct from another. Indeed, in the late 16th century, native lords of the Collaguas province in the south-central Peruvian highlands told their Spanish overseers that they bound the heads of their infants to mold them in the form of the mountain from which they descended. As layered as these indigenous testimonies are, studies that have treated them as windows into the prehispanic past unwittingly risk privileging the ethnopolitics of the colonial period.

By contrast, this book aims to dial back the clock four hundred years to uncover the long-term history of head shaping in the very region where the above-mentioned account was recorded. My analysis of human skeletal remains from Collagua cemeteries traces the practice’s rise in frequency in the centuries prior to Inka and Spanish colonialism. I show how the construction of a shared and embodied collective identity, while a basis for ethnic solidarity, also bred greater diversity of lived experiences and contributed to emerging social inequalities. Even individuals with the same head shape show marked variability in early childhood diet, practices of mobility, and evidence for violent encounters later in life. By situating cranial modification at the intersection of gender, kinship, and status, I argue for a more dynamic understanding of what it meant to be modified—one that takes into account other aspects of social identity beyond ethnicity and takes seriously the indigenous worldviews and practices that animated relations between bodies and mountains. Such an approach underscores how concepts of personhood are fundamentally political in nature, working to naturalize certain kinds of bodies as distinct and privileged.